Hello all.

I write this a few hours after returning from the second day of my internship. If this edition seems like its author is suffering from a stroke, it’s because he probably is. Who knew working for a high-powered US law firm would be so hard…

Also, I’m interviewing a few of you on Saturday for some marketing/editorial roles. If you want to be considered, hit my LinkedIn up. Should be fun.

With that being said, let’s dive in!

Outline

Too much M&A a dull boy makes - it’s time for a bankruptcy.

Today, I bring you Enron. These guys grew their stock price 311% in eight years, only to become insolvent three years after. I’m going to show you how a whole load of dodgy accounting and a few public errors by key executives led a company with over $60b of assets to nosedive into one of the largest bankruptcies of all time.

What to know how it ends?

Here’s a hint: this is a mugshot of one of their CEO’s, Kenneth Lay.

Timeline

1985: Houston Natural Gas and InterNoth merge to create Enron.

1990-2000: Congress has the ingenious idea of deregulating natural gas pricing, meaning Enron can charge whatever they want. They become the largest natural gas seller in the US, and diversify into water, broadband, and the very energy contracts they were selling to others. Genius. By 2000, Enron was trading at a market cap of $60b with a P/E ratio of 70 which is f****** nuts for a power company. Stock price is a high of $90.

September 2000: The Wall Street Journal writes a story criticising Enron’s accounting practices. Basically, they use mark-to-market accounting, where income is valued based on market prices, not on the price actually received. Sounds complicated - deal with it for now, more about this in the analysis section. No one pays attention yet.

March 2001: Fortune writes a story criticising Enron’s stock price on the basis that the company’s accounting was so vague that no one can trace where Enron gets its revenue from. Still, no one cares.

April 2001: Enron CEO Jeff Skilling calls an analyst questioning Enron’s accounts an ‘asshole’ on a conference call - bad idea. People start paying attention.

July 2001: Enron announce their earnings - profit margins low and these accounts are super vague. At this point, the stock price is down 30% year-on-year to $60. It’s blowup time.

October 2001: At this point, Enron is in full free-fall. They try to sell off failing business units, to no avail. Then, the SEC starts looking into suspicious selling of stock by the company’s executives - what a shock, a company with dodgy accounting also has really dodgy insider trades! Stock at $16, as loads of executives begin leaving and Enron credit is downgraded to just above junk status.

November 2001: A savior! Dynegy, rival energy firm, offers to buy Enron for a measly $8b. However, the deal would keep Enron alive.

December 2001: Enron manages to blow $5b in 50 days, leaving it broke. All credit agencies downgrade Enron to junk status, the SEC’s formal investigation looks to be immense in scope, and Dynegy pull out of the deal. Christ, if you think writing an essay the day of submission is stressful, imagine being one of the Enron executives. In the face of this catastrophe, Enron file for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy. With $63b of assets on their balance sheet, this becomes one of the largest bankruptcies of all time.

Aftermath: Enron’s accountants, Arthur Andersen, had employed some cheeky audit practices and had destroyed lots and lots of evidence. So, when Arthur Andersen got effectively dissolved, it came as no surprise. A few Enron execs went to prison, including CEO’s Kenneth Lay and Jeff Skilling. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act followed in 2002, which increased the standards of public company accounting and filings (whether this has been effective is a different question).

Honestly, reading this timeline is hilarious and saddening at the same time. It’s amusing to see how short-sighted Enron execs were in their accounting ploys, but I sober at the thought that, ultimately, it was the employees of Enron who lost all of their pensions and got no severance pay. As I said many moons ago, however, this is not a philosophy blog. Onwards.

Analysis

Issue 1: Mark-to-market

When Enron sold energy or entered into supply contracts with counterparties, they sought to hedge this risk by entering into derivatives contracts. Basically, if they sold loads of power to one person, they’d buy a similar amount of oil from another supplier to be market-neutral.

Sounds fair enough. Where this got really freaky was with the mark-to-market method that CEO Jeff Skilling introduced, because it allowed Enron to value those derivatives contracts based on the anticipated future values of the product being traded - in short, Enron could make the value up.

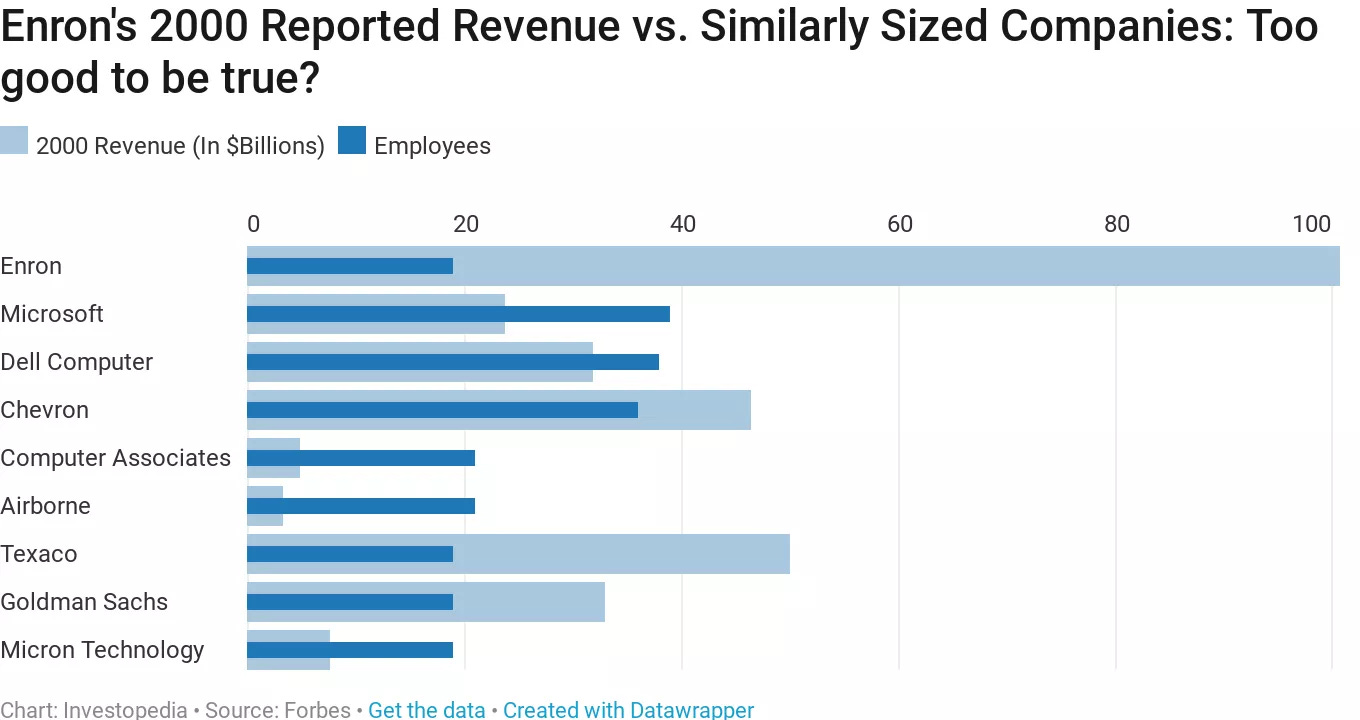

Look at this diagram:

Does that look like a healthy company? No, it’s as believable as Joe Biden speaking clearly for more than five sentences (love ya, Joe).

Mark-to-market accounting let Enron massively overestimate revenues, inflating Enron’s valuation far beyond what it should have been.

Issue 2: SPV’s

Special Purpose Vehicle = SPV. Basically, a shell company made for one purpose.

These bad boys are like the Swiss Army Knife of the corporate world. Want to hide the real owners behind a company? SPV. Want to transfer assets tax-free? SPV. Want to shift debt off your balance sheet? SPVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV.

And that last one is just what Enron did.

Investopedia sums it up nicely:

‘Enron would transfer some of its rapidly rising stock to the SPV in exchange for cash or a note. The SPV would subsequently use the stock to hedge an asset listed on Enron’s balance sheet. In turn, Enron would guarantee the SPV’s value to reduce apparent counterparty risk.’

However, Enron’s SPVs were solely filled with the stock of the company the SPV was trying to hedge in the first place. That was dumb idea. Why? If the stock falls, then the SPV no longer has enough collateral to pay off the debt, and it all collapses.

And that’s just what happened.

Issue 3: When your accountant is also your consultant

Wachtell, Goldman Sachs and McKinsey are all super prestigious and profitable, and have similar clients - why don’t they just combine into some massive entity?

Not only would that cause every LSE student to have a prestige-induced-aneurysm, but these types of combinations are also ILLEGAL. Why? Conflicts of interest. You can’t receive consulting, legal and financial advice from one firm because the interests of the parties become misaligned.

Arthur Andersen, however, was providing Enron with consulting and auditing services. Whilst consultants are paid to think big (and often moronically, looking at you McKinsey and CNN+), auditors are paid to ensure a company is not getting too big for its proverbial boots by misstating how much money they’re making etc.

In short, Arthur Andersen’s auditors were incentivised to allow Enron to fake revenue, because their consulting arm benefited from it. Not a good idea.

Key takeaway: deregulation sometimes works. In the case of public filings, accounting, and energy sales, it definitely didn’t.

Thank you for reading!

Christ, writing on 4 hours sleep, broken by a day of M&A law and overpriced bagels, really is a trip.

Still had a great time writing, and we cracked 500 subs yesterday! Thanks to you all, truly.

Next step: 1k.

Love,

Alex

Further readings

Investopedia, ‘Enron Scandal: The Fall of a Wall Street Darling’

The New York Times, ‘An Implosion on Wall Street’

Not much else on this beyond these bad boys, sorry.